This year I’m in a Humanities class. To finalize the semester, each student presents a “Creative Project.” The project includes a 10-15 line recitation from one of the texts we’ve read, a supplement (art piece, sculpture, song, dance, etc.), and a 5-7 minutes talk.

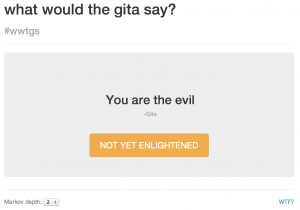

I’m reciting a passage from the Bhagavad Gita and was at a loss of what to include as a supplement until I remembered What Would I Say.

What Would I Say is a project by HackPrinceton which creates a Markov chain from your Facebook statuses and uses it to generate sentences that sound like you. The results are “often hilarious (and sometimes nonsensical).” I decided that as my supplement I wanted to create a Markov chain of the Bhagavad Gita, the goal being to generate phrases that sound like they were pulled from the text but really make little to no sense. This ended up being easier than I expected. Steps are as follows.

- Extract the text from the Bhagavad Gita into plaintext

- I had a PDF copy so extracting just the text was tough, but after half an hour or so of regular expressions and manual editing, it was fine

- Create a Markov chain from the result

- I used codebox’s markov-chain project from GitHub

- I initially only generated the chain with a depth of 3, but added chains of depth 2 and 4 later — depth 2 produces far more disjointed and ridiculous sentences, depth 4 produces almost verbatim sentences with occasional changes

- Get a nice template

- Shamelessly copied from What Would I Say

- Programatically make random sentences available through an API

- I modified the markov-chain project slightly and put it inside a Flask wrapper

- Write some JavaScript to grab new results from the API when the big button is clicked

That’s it! The final result can be seen at instantgita.com and works pretty nicely. The Markov chain depth defaults to 3, but it’s worth playing with 2 and 4 as well.

]]>

The Android SDK contains a tool called monkeyrunner. Monkeyrunner lets you simulate touch events, take screenshots, etc… and it does it through a very simple Python library. I decided to see if I could write a little script to keep pressing the ice cream button in Uber’s app, and it only took a few minutes.

from time import sleep

from com.android.monkeyrunner import MonkeyRunner, MonkeyDevice

# Attach to Android device

d = MonkeyRunner.waitForConnection()

# Take a screenshot of the "sorry, keep trying" screen for reference

raw_input("Get to the error screen, then hit enter.\n")

oldpic = d.takeSnapshot()

while True:

# Touch the ice cream button

d.touch(540, 200, MonkeyDevice.DOWN_AND_UP)

sleep(4)

newpic = d.takeSnapshot()

# If the screen looks like our old error

# screen (95%), hit OK and just keep going (in 10 seconds)

if newpic.sameAs(oldpic, .95):

d.touch(460, 700, MonkeyDevice.DOWN_AND_UP)

sleep(10)

# But if the screen has changed, stop running the loop.

else:

break

I still don’t have ice cream, but the script is running and working.

]]>The other day I saw something as part of a commercial spoofing service that I hadn’t seen before: bidirectional caller ID spoofing. Basically, it will call friend A from friend B’s number, friend B from friend A’s number, and record the result. This leads to something along the lines of “You called me!” “No, you called me!” As fun as that is, websites like PrankDial are charging a lot of money to do something that is, in practice, very simple.

I haven’t seen a script to do this posted on the internet yet, so I created one and put it on github. You’ll have to set up the Asterisk server by yourself, but implementing the script is easy.

- Put dual_cid_spoof.py in the /usr/share/asterisk/agi-bin directory

- Make it executable to the asterisk user

- Add an extension to extensions.conf that calls the script, using pattern matching to give it arguments. For example:

[spoof]

exten => _37NXXNXXXXXXNXXNXXXXXX,1,Answer

exten => _37NXXNXXXXXXNXXNXXXXXX,2,AGI(dualcidspoof.py,${EXTEN:2:10},${EXTEN:12:10})

This uses the extension 37, but that part can be changed. This pattern matches any calls that have the number 37 followed by two 10-digit phone numbers, and then pulls those numbers out and uses them as arguments to the AGI script ${EXTEN:2:10} means take the extension, at index 2, and pull out 10 digits. To execute it with phone numbers 123-123-1111 and 222-202-2020, I would dial 3712312311112222022020.

MeetMe is required to use this script, since it works by placing both users into a conference room together. The default conference room number is 1234, but that can be changed in the script. Also necessary is changing the outgoing SIP trunk in the Python script from “flowroute” to whatever the name of your outgoing SIP trunk is. Both of these are variables at the top of the script. Execution flow works like this:

- Create two .call files, each with opposite CID/destination info. These files are set to dump the callees into a conference room when they answer.

- Place the files in /var/spool/outgoing/asterisk, to be automatically processed by the Asterisk spooler.

- Connect you into the same conference room as a muted admin, giving you the ability to kick users and listen without being heard.

Enjoy, and feel free to ask questions. Again, you can get the script here.

]]>Around two years ago, a fellow by the name of darco posted an article called “Hacking Christmas Lights” on his blog. He was nice enough to reverse engineer the LED data bus protocol of the GE Color Effects christmas lights, as well as release some code for an ATMel microcontroller. This was of course turned into an Arduino library soon after.

I had an idea for something to do with these lights: I wanted a network service I could connect to which would pick a random color from a pre-defined list, tell me which color it picked, and then “push” that color onto the string of lights. Each time the service was hit, a new color would enter the string of lights. Each other color would move to the next light until it was at the end of the string, where it would “fall off.”

I decided to do all the networking and color choosing in a Python script on my laptop, leaving the Arduino with just the task of controlling the lights and storing their colors. The GEColorEffects library would handle the control, so all I needed to do on that end was find a data structure to store the colors in. Usually I would just use an array, but this approach gets ugly when you want to “move” each color to the next light. It would involve copying every single color value in the array to the next location before adding the new color.

// colors are 12 bits, so can be stored in a 16-bit type easily

uint16_t lights[NUMLIGHTS]; // populated somewhere else in code

int i;

--snip--

for (i = NUMLIGHTS; i > 1; i--) {

lights[i-1] = lights[i-2];

}

lights[0] = newcolor;

The previous code would have to be called every time I wanted to add a new color to the string of lights. It would probably work just fine (meaning sufficiently fast) considering that it’s only copying 72 bytes, but it feels clunky. I wanted an approach which felt elegant. The thing that came to mind after some shower-aided thinking (all good programming ideas happen in the shower) was a circular linked list. A linked list is a collection of structures, 0r collections of data, with the unique characteristic that each structure contains a pointer to the next one. In a doubly-linked list, each structure contains a pointer to the previous and the next one. In a circular linked list, the last structure points to the first, effectively making it act like a circle. If you were to follow the path forever, you’d never reach an end.

The nice part of using circular linked lists is that you can just choose where the “beginning” is dynamically.

struct RGB

{

// each color is only 4 bits but stored as an 8-bit type

uint8_t r;

uint8_t g;

uint8_t b;

struct RGB *next; // pointer to the next RGB structure

};

typedef struct RGB rgb;

rgb *head;

void populate_linked_list()

{

int i;

rgb *curr;

curr = head = (rgb*)malloc(sizeof(rgb)); // allocate first struct as head

for (i = 0; i < lightCount-1; i++) { // allocate 35 more (36 lights total)

curr->r = 15; // they all start out red

curr->g = curr->b = 0;

curr->next = (rgb*)malloc(sizeof(rgb));

curr = curr->next;

}

// and finally, the last struct

curr->r = 15;

curr->g = curr->b = 0;

curr->next = head; // the "next" after the last, is the first

curr = head;

}

The lights are set by iterating through the list and using the GEColorEffects library to set each light to the color represented by each structure. Here comes the fun part. To “push” a color onto the set of lights (and move each other color to the next light), all you have to do is write the color values to the current head of the list, and then move the head to point to the next structure. Keep in mind that we’re pushing colors onto the end of the list, and each color at the very beginning of the list falls off when we do that.

void add_color(uint8_t r, uint8_t g, uint8_t b)

{

head->r = r;

head->g = g;

head->b = b;

head = head->next;

}

We’ve just moved the beginning/head of the list one light forward (meaning the 2nd color on the string of lights moves to the 1st, 3rd moves to 2nd etc.) and put the data for the new color in the previous location of the head, which is now the very end of the list. The colors of the lights appear to move accordingly.

I put the code on github here. It comes with the Arduino sketch which implements the linked list setup as well as a simple serial interface. Read the README for more info about that.

]]>Cory Doctorow captures what I’m saying in a quote from his book Little Brother:

If you’ve never programmed a computer, you should. There’s nothing like it in the whole world. When you program a computer, it does exactly what you tell it to do. It’s like designing a machine — any machine, like a car, like a faucet, like a gas-hinge for a door — using math and instructions. It’s awesome in the truest sense: it can fill you with awe.

A computer is the most complicated machine you’ll ever use. It’s made of billions of micro-miniaturized transistors that can be configured to run any program you can imagine. But when you sit down at the keyboard and write a line of code, those transistors do what you tell them to.

Most of us will never build a car. Pretty much none of us will ever create an aviation system. Design a building. Lay out a city.

While the quote discusses programming specifically, it explains the brilliance of using the tools available to you to invent new tools. Check out a hackerspace near you, or the MAKE homepage, or Hack-A-Day. Look at all the links in this single post: all people who make things and want to help others do the same.

Go make something.

]]>

I’d like to extend a thank you to San Francisco’s Noisebridge hackerspace for being so hospitable and friendly towards me during my time here. On Friday when I arrived in SFO, I took the BART straight to Noisebridge and hung out there till that night. It was nice to be in an environment where I could work, learn, and talk, despite being a stranger in this city.

I’ve met a lot of interesting people and was even invited out to dinner that night. San Franciscans really love their lights, I’ve found. Our crepe restaraunt had fancy fading rainbow lights.

I’ve included a picture of Noisebridge at a fairly dormant time.

]]>Fulgurites are the figures made by lightning hitting sand (or other melty grainy materials). We don’t have lightning but we can definitely simulate it with the pole pig. We start by putting sand (100lb for $7 at Home Depot) in a terracotta pot. We stick electrodes from the transformer straight into the pot and turn it on. The result comes out like this.

We then epoxy them into nice solid pieces of art. I made a video about the process for my science class.

Fulgurite Production at Hackerbot Labs from Nick Mooney on Vimeo.

Credits to Pip aka @yoyojedi for helping me out with this. He’s the fulgurite master and was nice enough to teach me how.

]]>When the phone arrived I went through the fairly standard procedure: wipe data from old phone, keep battery/card/back-cover, install them in new phone and activate by dialing *228. In a few minutes after waiting on crappy activation music, it was done. My phone instantly picked up a signal and I went on my merry way packaging up the old phone to send back.

I started to notice some weird things that night though. The first was that I was told I had to dial the area code while ‘roaming’. This was weird, but I figured dialing *22899 to refresh the cell tower data would fix it. No luck though. Oh well– it’ll sort itself out. Then I started getting messages from my friends asking why I wasn’t answering my phone. I decided to run an experiment by calling my home phone from my cell. The caller ID showed up as a 410 area code (Maryland). It was bidirectional too, meaning my phone rang when I called the Maryland number. My old local number went straight to voicemail.

I called up Verizon and told them about the issue, and the rep I had was very confused by the situation. I was put on hold a couple times and told that he would have to converse with a higher-up. Verizon claims that they can’t program the phone remotely to my correct number and decide to ship me yet another new phone, same as last time. Meanwhile, I have no access to my old number and some poor soul in Maryland probably wants their number back. I can make and receive calls on this Maryland number, and Verizon recognizes me as the person on that account. Luckily though, it was secure enough such that I couldn’t make any account changes without the social security number.

The new (Droid #4) phone is set to arrive tomorrow, and hopefully it’ll work just fine. I’ll have 3 Droids in the house then… but I have to send 2 of them back via prepaid FedEx.

]]>The Robot Arm project has been gathering some dust for a while. Code is a little slow to develop since I can only access the arm itself on Saturdays. That said, however, I’ve fixed a problem! To connect to the Gamoto motor control board, I need a USB-Serial adapter and then a janky-as-shit serial-to-Gamoto adapter which connects to some protoboard, which connects finally to the Gamoto. I learned Saturday that I rushed my first job in creating the janky-as-shit serial-to-Gamoto adapter and barely connected the wire to the correct pin. It was a cold solder joint, so I made a new adapter, and I wanted to share a trick that some people might not know.

When soldering wires to headers (sets of pins), you can put the bottom of the header in a protoboard, hook the wire around the pin, and solder like that. It works really well and is much easier than soldering without the hook.

Anyways, code will be posted soon. It’s currently being edited constantly in an effort to improve/optimize/extend. This is my first real Python project so I’m learning all the time.

]]>

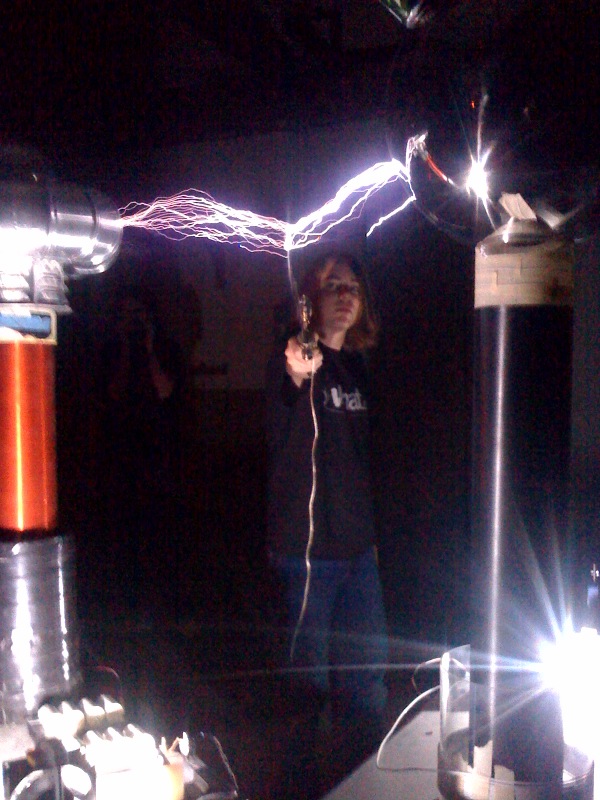

Catching lightning from two tesla coils

At the lab we have 3 tesla coils owned by different members. We decided to put them all in one room. Chaos SCIENCE ensued! This is a picture of me catching lightning with a grounded sword. In simple terms: there’s a wire attached to the sword, which is attached to ground. The tesla coil electricity travels through the wire, and not me.

Hopefully, more on tesla coil stuffs later.

]]>